Autoimmune uveitis is a serious eye condition where the body’s own immune system attacks the uvea - the middle layer of the eye that includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Unlike infections or injuries, this inflammation isn’t caused by germs or trauma. It’s an internal misfire. Left unchecked, it can lead to permanent vision loss through complications like glaucoma, cataracts, or retinal detachment. And while corticosteroids are the first line of defense, long-term use brings its own dangers. That’s why steroid-sparing therapy has become a critical part of modern treatment.

What Exactly Is Autoimmune Uveitis?

Uveitis means inflammation of the uvea. When it’s autoimmune, your immune system mistakes parts of your eye for foreign invaders. This can happen without any obvious trigger. Symptoms often appear suddenly: redness, eye pain, blurred vision, sensitivity to light, floaters, or headaches. These can affect one or both eyes. Some people notice changes over days; others wake up with severe symptoms.

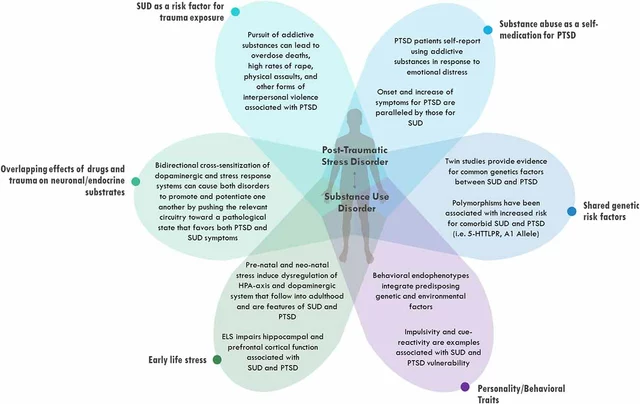

It’s not just an eye problem. Autoimmune uveitis is often tied to systemic diseases. About half of all cases are linked to conditions like ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, or sarcoidosis. That’s why diagnosis isn’t just about looking in the eye - it’s about understanding the whole body. Blood tests, imaging like OCT and fluorescein angiography, and a full medical history are all part of the puzzle.

The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) confirms that distinguishing autoimmune uveitis from infectious causes is essential. Treating an infection with immunosuppressants can make things worse. That’s why a thorough workup by an ophthalmologist - often within 24 hours of symptom onset - is non-negotiable.

Why Steroids Are Used - and Why They’re Problematic

Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatories. For acute uveitis, they work fast. Eye drops are used for front-of-the-eye inflammation. Injections near or into the eye help with deeper inflammation. Oral steroids are reserved for severe or widespread cases.

But here’s the catch: long-term steroid use causes real harm. Cataracts form more quickly. Eye pressure rises, leading to glaucoma. Weight gain, high blood sugar, bone thinning, mood swings, and increased infection risk are common side effects. For someone with uveitis that flares repeatedly - which is common - steroid dependence becomes a trap.

The Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) puts it plainly: steroid-sparing therapy becomes essential for chronic management. You can’t keep using steroids forever. The goal isn’t just to calm the inflammation - it’s to do it without wrecking the rest of your body.

Steroid-Sparing Therapy: What It Is and How It Works

Steroid-sparing therapy means using other drugs to control inflammation so you can reduce or stop steroids entirely. These aren’t experimental - they’re backed by years of clinical use and now FDA approval.

The most well-known is adalimumab (Humira). In 2016, the FDA approved it for non-infectious uveitis - the first biologic drug ever approved for this use. It blocks TNF-alpha, a protein that drives inflammation. Studies show it reduces flare-ups and cuts steroid use by up to 70% in many patients. Dr. Nisha Acharya at UT Southwestern documented its success in pediatric cases, with kids showing strong response and less steroid dependence.

Other options include:

- Methotrexate: An older immunosuppressant, often used for autoimmune conditions. It’s taken weekly and requires regular blood tests.

- Cyclosporine: Works by suppressing T-cells. Effective but can affect kidney function, so monitoring is key.

- Infliximab: Another TNF inhibitor, given by infusion. Used when adalimumab doesn’t work or isn’t tolerated.

- Other biologics: Drugs targeting IL-6, JAK pathways, and other immune signals are in clinical trials and showing promise for resistant cases.

The Cleveland Clinic stresses that treatment must be tailored. A patient with uveitis linked to Crohn’s disease might respond better to a drug already used for gut inflammation. Someone with no systemic disease might need a different approach. There’s no one-size-fits-all.

Who Needs Steroid-Sparing Therapy?

Not everyone needs it right away. For a single, mild episode of anterior uveitis, steroids alone may be enough. But steroid-sparing therapy is recommended if:

- You’ve had multiple flare-ups in the past year

- You need high-dose steroids for more than 3 months

- You develop steroid side effects like cataracts or high eye pressure

- Your uveitis is linked to a systemic autoimmune disease

- You’re a child or young adult - where long-term steroid exposure is especially risky

Patients with posterior or panuveitis - inflammation in the back of the eye - are more likely to need these drugs early. The inflammation is harder to reach with eye drops, and the risk of permanent damage is higher.

UT Southwestern notes that because uveitis affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S., most treatments are still considered off-label. That’s why Humira’s approval was such a milestone - it gave doctors a clear, standardized option.

The Role of Rheumatologists and Ophthalmologists

This isn’t just an eye doctor’s problem. It’s a team sport.

Autoimmune uveitis often overlaps with rheumatologic conditions. A rheumatologist can help identify the underlying disease, manage systemic symptoms, and choose the best immunosuppressant. An ophthalmologist monitors eye health, checks for complications, and adjusts local treatments.

The NCBI highlights that clinical collaboration between these specialists is critical. Patients who see both do better - fewer flares, lower steroid use, and less vision loss. That’s why specialized uveitis clinics have grown from 15 in 2010 to over 50 in 2023 across major U.S. hospitals.

If you’re diagnosed with autoimmune uveitis, ask for a referral to a uveitis specialist. Don’t settle for general eye care if your condition is complex or recurrent.

What to Expect When Starting Steroid-Sparing Therapy

These drugs don’t work overnight. It can take weeks or months for them to build up in your system and start controlling inflammation. During that time, you’ll likely still need steroids - but the goal is to taper them slowly as the new drug kicks in.

Side effects vary. Methotrexate can cause nausea and fatigue. Cyclosporine may raise blood pressure or affect kidneys. Biologics like Humira increase infection risk - you’ll need to avoid live vaccines and report fevers or unusual symptoms right away.

Regular follow-ups are non-negotiable. You’ll need eye exams every few weeks at first, then every 3-6 months. Blood tests check liver and kidney function, blood counts, and signs of infection. The NHS recommends these visits not just to track treatment, but to catch complications like vision loss early.

Many patients report improved quality of life once they’re off high-dose steroids. Less weight gain, better sleep, fewer mood swings. But new challenges come with immunosuppression. You’ll need to be more careful around sick people, wash hands often, and stay up to date on vaccines - except live ones.

The Future of Uveitis Treatment

The field is moving fast. Seven new biologics targeting different parts of the immune system are in clinical trials. Researchers are exploring drugs that block interleukin-17, IL-6, and the JAK-STAT pathway. These could help patients who don’t respond to TNF inhibitors.

Precision medicine is on the horizon. Genetic markers and blood biomarkers may soon help predict who will respond best to which drug. Instead of trial and error, doctors could match therapy to biology.

For now, the standard is clear: control inflammation quickly with steroids, then transition to steroid-sparing therapy to protect your eyes - and your body - long-term. The goal isn’t just to preserve vision. It’s to let you live without the burden of chronic medication side effects.

When to Seek Help

If you have any of these symptoms, see an eye doctor immediately:

- Sudden eye redness with pain

- Blurred vision that doesn’t clear up

- Floaters that increase suddenly

- Extreme sensitivity to light

- Headache along with eye discomfort

Don’t wait. Delayed treatment increases the risk of permanent damage. If you’ve been diagnosed before and symptoms return, don’t assume it’s just a flare-up - get checked. Recurrent uveitis needs a different strategy.

Is autoimmune uveitis curable?

Autoimmune uveitis is not curable, but it is manageable. With the right treatment plan - especially steroid-sparing therapy - most patients can control inflammation, prevent vision loss, and live without long-term steroid use. Flares can still happen, but they become less frequent and less severe over time.

Can I stop steroids completely with steroid-sparing therapy?

Many patients can reduce or stop steroids entirely, but it depends on the individual. Some need a low dose long-term for stability. The goal isn’t always zero steroids - it’s the lowest possible dose that keeps inflammation under control while avoiding side effects.

Are biologic drugs like Humira safe for long-term use?

Biologics have risks - mainly increased infection and rare immune-related side effects. But for most patients with chronic uveitis, the benefits outweigh the risks. Regular monitoring and avoiding live vaccines help manage safety. Long-term data from over 8 years of use shows most patients tolerate them well when followed closely by their care team.

What happens if steroid-sparing therapy doesn’t work?

If one drug fails, another may work. There are multiple classes of immunosuppressants and biologics. Doctors often switch or combine therapies. Newer drugs targeting different immune pathways are being tested for patients who don’t respond to TNF inhibitors. Clinical trials are an option for those with refractory cases.

Can children be treated with steroid-sparing therapy?

Yes, and it’s often necessary. Children are more vulnerable to steroid side effects like growth delay and bone loss. Drugs like adalimumab and infliximab have been studied in pediatric uveitis and shown to be effective with good safety profiles when monitored closely by specialists.

Do I need to see a specialist, or can my regular eye doctor handle this?

If your uveitis is mild and single-time, a general ophthalmologist may manage it. But if it’s recurrent, involves the back of the eye, or is linked to another autoimmune disease, you need a uveitis specialist. These doctors work closely with rheumatologists and have the experience to navigate complex cases and newer treatments.

Comments(14)