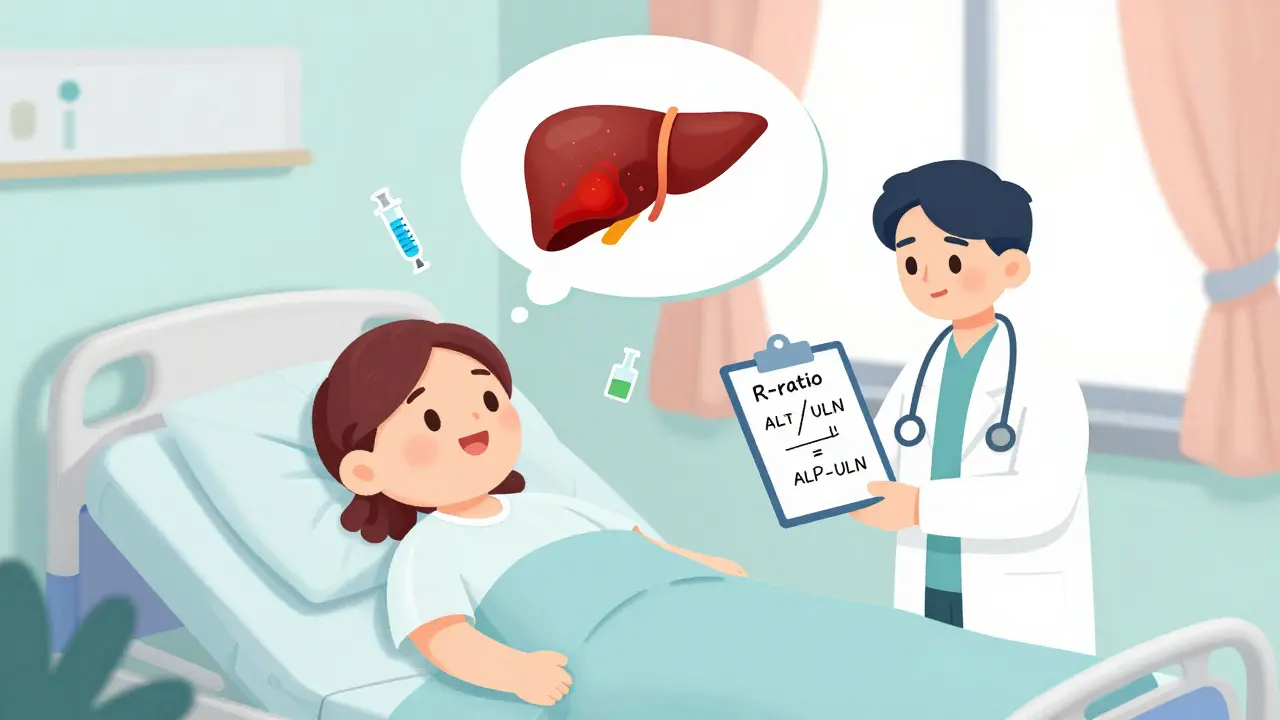

R-Ratio Calculator for Antibiotic Liver Injury

The R-ratio helps distinguish between hepatitis (ALT-driven) and cholestasis (ALP-driven) patterns of antibiotic-induced liver injury. Calculate your ratio using lab values.

Results

Enter your lab values to see results.

Key Interpretation:

- R-ratio > 5: Hepatitis pattern

- R-ratio < 2: Cholestasis pattern

- R-ratio 2-5: Mixed pattern

Antibiotics save lives. But for some people, the very drugs meant to fight infection can quietly damage the liver-sometimes without warning. If you’ve been on antibiotics for more than a week and suddenly feel unusually tired, notice yellowing in your eyes, or have dark urine, it might not just be the infection getting worse. It could be your liver sending a signal. Antibiotic-related liver injury is one of the most common causes of drug-induced liver damage, accounting for 64% of all cases seen in intensive care units. This isn’t rare. It’s common, underrecognized, and often missed.

How Antibiotics Hurt the Liver

Not all antibiotics cause liver injury, but many do-and in different ways. The damage usually shows up in two patterns: hepatitis and cholestasis. Hepatitis means the liver cells themselves are being damaged. You’ll see a big spike in ALT (alanine aminotransferase), a liver enzyme that leaks out when cells die. Cholestasis is different. Here, bile flow gets blocked. That’s when ALP (alkaline phosphatase) rises sharply. Sometimes, you get both-a mixed pattern.The key to telling them apart? The R-ratio. It’s a simple formula: peak ALT divided by ULN, then divided by peak ALP divided by ULN. If the result is above 5, it’s mostly hepatitis. Below 2, it’s cholestasis. Between 2 and 5? Mixed. This isn’t just academic-it guides what doctors do next.

How does this happen? Antibiotics can mess with your liver cells in a few ways. Some block energy production in mitochondria-the power plants inside your cells. Others create toxic byproducts that burn liver tissue. Then there’s the gut. Antibiotics wipe out good bacteria, letting bad ones take over. That weakens the gut lining, letting toxins flow straight to the liver. Your liver, already busy processing the drug, gets hit with a double blow.

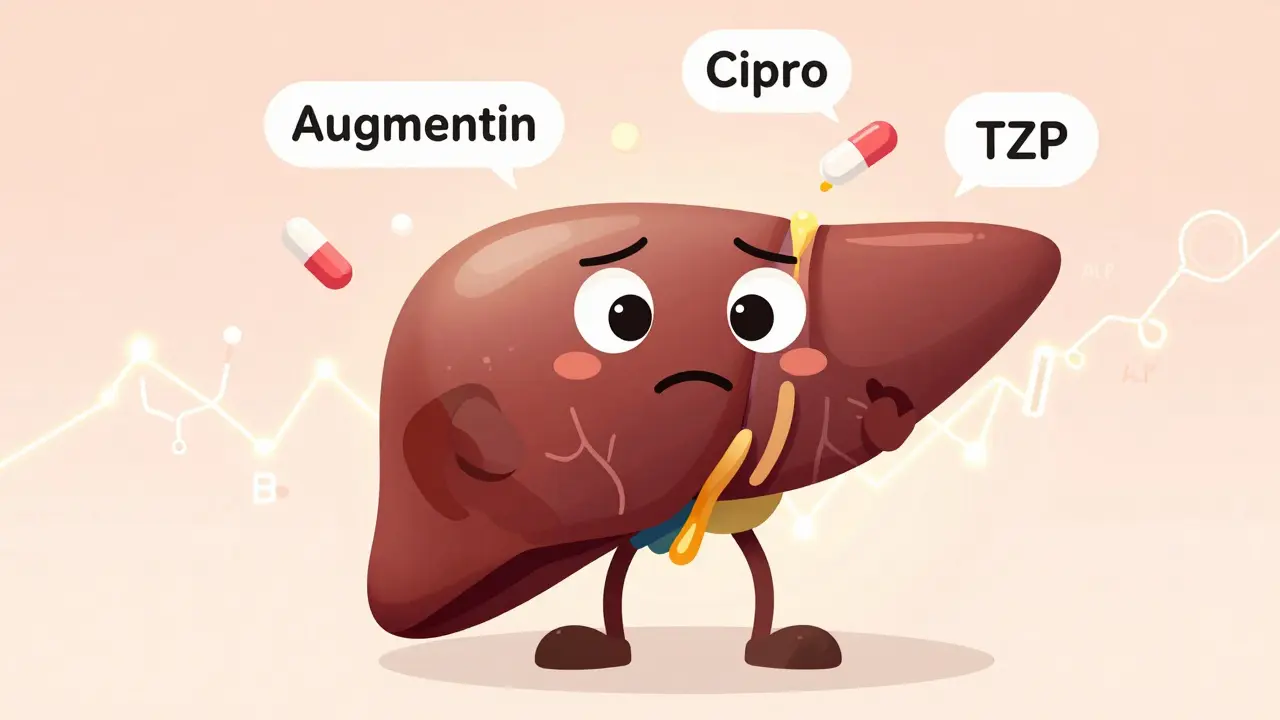

Which Antibiotics Are Most Likely to Cause Problems?

Some antibiotics are far riskier than others. Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin) tops the list. About 15 to 20 out of every 100,000 people who take it develop liver injury. In about 70-80% of those cases, it’s cholestatic-bile flow slows down. The injury usually shows up 1 to 6 weeks after starting the drug.Fluoroquinolones like ciprofloxacin and azithromycin are trickier. They tend to cause mixed injury, with both ALT and ALP rising. These can strike faster-sometimes within just 1 to 2 weeks.

Then there’s piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP), a go-to antibiotic in hospitals for serious infections. A 2024 study found that nearly 29% of ICU patients on TZP for 7+ days developed liver injury. Compare that to meropenem, another common ICU antibiotic, where the rate was just over 12%. And here’s something surprising: men on meropenem are 2.4 times more likely than women to get liver damage.

Rifampin, used for tuberculosis, causes dose-related injury. Too much, too long, and your liver can’t handle the buildup of toxic intermediates. Even worse? When rifampin is paired with isoniazid (a TB drug), the risk skyrockets.

Not all antibiotics are equal. Nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole fall into the moderate-risk category. Vancomycin and penicillin? Low risk. But don’t assume safety just because a drug is common. If you’re on it for more than a week, especially in the hospital, your liver needs watching.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. Your body matters too.If you’re in the ICU with sepsis, your risk of antibiotic-related liver injury jumps by 80%. Why? Your body is already under massive stress. The liver is fighting inflammation, infection, and now a drug. It’s a perfect storm.

Age plays a role. Older adults clear drugs slower. Their livers are more fragile. Women are more likely to get cholestatic injury. Men? More prone to hepatocellular damage, especially with drugs like meropenem.

Genetics might be the biggest hidden factor. Research now shows certain HLA gene variants make some people far more susceptible to idiosyncratic (unpredictable) liver injury. This isn’t about dose-it’s about your DNA. That’s why two people on the same antibiotic, at the same dose, can have wildly different outcomes.

And here’s a new frontier: your gut microbiome. A 2022 study found that people with low levels of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a beneficial gut bacterium, had a 3.7-fold higher risk of developing liver injury after antibiotics. That’s not just correlation-it’s a potential warning sign.

What Does It Feel Like?

Many people have no symptoms at all. The first clue? A routine blood test shows elevated liver enzymes. That’s why monitoring matters.When symptoms do show up, they’re vague-easy to blame on the infection itself. Fatigue. Nausea. Loss of appetite. Aching in the upper right abdomen. Then, if it gets worse: yellow skin or eyes (jaundice), dark urine, pale stools, itching. These aren’t normal side effects. They’re red flags.

In severe cases, people develop acute liver failure. That’s rare, but it happens. And the only way to stop it? Stop the antibiotic. Immediately.

How Doctors Diagnose and Monitor It

There’s no single test for antibiotic-induced liver injury. It’s a diagnosis of exclusion. That means doctors have to rule out everything else: viral hepatitis, gallstones, heart failure, alcohol damage, autoimmune disease.Here’s what they do:

- Check liver enzymes before starting the antibiotic-baseline is key.

- Repeat tests after 1-2 weeks for high-risk drugs like Augmentin.

- For ICU patients on long courses (7+ days), test weekly.

- Look at the R-ratio to classify the pattern.

- Watch for rising bilirubin and symptoms.

The rule of 5? Many doctors use it: if ALT is more than 5 times the upper limit of normal, or ALP is more than 2 times normal and you have symptoms, stop the drug. But it’s not absolute. In critically ill patients, sometimes you can’t stop the antibiotic-even if the liver is hurt. That’s the brutal trade-off.

What Happens After Stopping the Drug?

Good news: most people recover fully. Liver enzymes usually drop back to normal within 2 to 8 weeks after stopping the antibiotic. Recovery is faster with cholestatic injury than with severe hepatitis.But not everyone recovers. About 1 in 10 people develop chronic liver damage. A small number need a transplant. That’s why early detection is everything.

There’s no antidote. No miracle supplement. No herbal cure. The only proven treatment? Stop the drug and give the liver time to heal. Supportive care-hydration, rest, avoiding alcohol and other liver stressors-is all that’s needed in most cases.

What’s Changing in 2026?

The field is moving fast. Researchers are now testing probiotics to protect the gut microbiome during antibiotic therapy. Early trials show promise in reducing liver enzyme spikes.Pharmacogenomics is the next big leap. Within 5 to 7 years, we may be able to test your HLA genes before prescribing antibiotics. If you carry a high-risk variant, your doctor could avoid Augmentin or TZP altogether and pick a safer alternative.

Companies are also developing stool tests to measure your gut bacteria before and after antibiotics. Low F. prausnitzii? That could trigger closer monitoring or even preventive probiotics.

The FDA and EMA are tightening safety guidelines. New antibiotics now require more rigorous liver safety data before approval. And post-marketing surveillance is more aggressive than ever.

What You Can Do

If you’re prescribed an antibiotic:- Ask: Is this the right drug for my infection? Are there lower-risk options?

- Ask: How long do I need to take this? Avoid unnecessary long courses.

- Know the signs: fatigue, nausea, yellowing skin, dark urine.

- Get baseline liver tests if you’re on high-risk antibiotics or have other liver risks.

- Don’t ignore mild symptoms. Report them early.

Don’t assume antibiotics are harmless because they’re common. They’re powerful. And your liver is working overtime to clean them up. Respect that. Your body isn’t just fighting infection-it’s fighting the cure, too.

Can antibiotics cause jaundice?

Yes. Jaundice-yellowing of the skin and eyes-is a classic sign of cholestatic liver injury from antibiotics. It happens when bile flow is blocked, causing bilirubin to build up in the blood. This is most common with drugs like amoxicillin-clavulanate and can appear weeks after starting treatment. Jaundice is not normal and requires immediate medical attention.

How long after taking antibiotics does liver damage appear?

Timing varies by drug. Amoxicillin-clavulanate usually causes injury 1 to 6 weeks after starting. Fluoroquinolones like ciprofloxacin can trigger damage in just 1 to 2 weeks. Some cases appear even after stopping the drug. There’s no fixed timeline-so monitoring during and after treatment is critical.

Are there any safe antibiotics for people with liver disease?

Some antibiotics are safer than others for people with pre-existing liver conditions. Penicillin, erythromycin (in standard doses), and cephalexin are generally considered low-risk. But no antibiotic is completely risk-free. Always inform your doctor about your liver history. They may choose a lower-dose regimen or monitor your liver enzymes more closely.

Can liver damage from antibiotics be reversed?

In most cases, yes. Once the antibiotic is stopped, the liver begins to repair itself. Liver enzymes typically return to normal within 2 to 8 weeks. Recovery is faster with cholestatic injury. However, in about 10% of cases, damage becomes chronic. Severe cases can lead to liver failure-making early detection vital.

Should I avoid antibiotics if I’m worried about my liver?

No. Antibiotics are life-saving when you have a serious bacterial infection. The risk of liver injury is low for most people. The key is smart use: take only what’s necessary, for the shortest time possible, and get monitored if you’re on a high-risk drug or have other risk factors. Don’t refuse needed treatment-but do ask questions and stay alert to symptoms.

Comments(13)