Beta-Blocker & CCB Combination Safety Calculator

When doctors prescribe beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers together, it’s not just adding two drugs-it’s mixing two powerful forces that can either save a heart or stop it. This combination isn’t common, but when used, it’s for serious cases: stubborn high blood pressure, angina that won’t quit, or certain irregular heart rhythms. The problem? The benefits are real, but so are the risks. And not all calcium channel blockers are created equal. One type can be safe; another can be dangerous-sometimes deadly.

How Beta-Blockers and Calcium Channel Blockers Work

Beta-blockers, like metoprolol or propranolol, work by blocking adrenaline. This slows your heart rate, lowers blood pressure, and reduces how hard your heart pumps. They’ve been around since the 1960s and are still widely used, especially for people with high heart rates or a history of heart attacks.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) work differently. They stop calcium from entering heart and blood vessel cells. This relaxes arteries, lowers blood pressure, and reduces the heart’s workload. But here’s the catch: not all CCBs act the same. There are two main types-dihydropyridines (like amlodipine and nifedipine) and non-dihydropyridines (like verapamil and diltiazem).

Dihydropyridines mostly affect blood vessels. They’re great for lowering blood pressure without much impact on the heart’s rhythm. Non-dihydropyridines? They hit the heart hard. They slow down electrical signals and reduce how strongly the heart contracts. That’s useful for some arrhythmias, but when paired with a beta-blocker? That’s where things get risky.

The Dangerous Synergy: When Two Drugs Become Too Much

Combining a beta-blocker with a non-dihydropyridine CCB-like verapamil or diltiazem-is like stepping on both the gas and the brake at the same time. Both drugs slow the heart’s electrical system. Together, they can cause:

- Severe bradycardia (heart rate below 50 bpm)

- Heart block (where signals from the top of the heart don’t reach the bottom)

- Worsening heart failure due to reduced pumping power

A 2023 study of over 18,000 patients found that verapamil plus a beta-blocker caused dangerous heart rhythm problems in 10-15% of cases. One patient in that study, an 82-year-old with a borderline PR interval, went into complete heart block just weeks after starting the combo. He needed a pacemaker. That’s not rare. It’s predictable.

Even in people without known heart issues, this combo can drop the left ventricular ejection fraction-how well the heart pumps blood-by 15-25%. That’s a huge drop. For comparison, either drug alone might lower it by 5-8%. The effect isn’t subtle. It’s measurable, dangerous, and often missed until it’s too late.

The Safer Option: Beta-Blockers + Dihydropyridine CCBs

Now, here’s the good news: when you pair a beta-blocker with a dihydropyridine CCB-like amlodipine-the risks drop dramatically. Amlodipine barely touches heart rhythm. It just opens up blood vessels. Studies show this combo is well-tolerated in most patients.

In a 2023 analysis of 18,681 hypertensive patients, those on metoprolol + amlodipine had:

- 17% lower risk of heart attack or stroke

- 28% lower risk of developing heart failure

- Far fewer cases of bradycardia or heart block

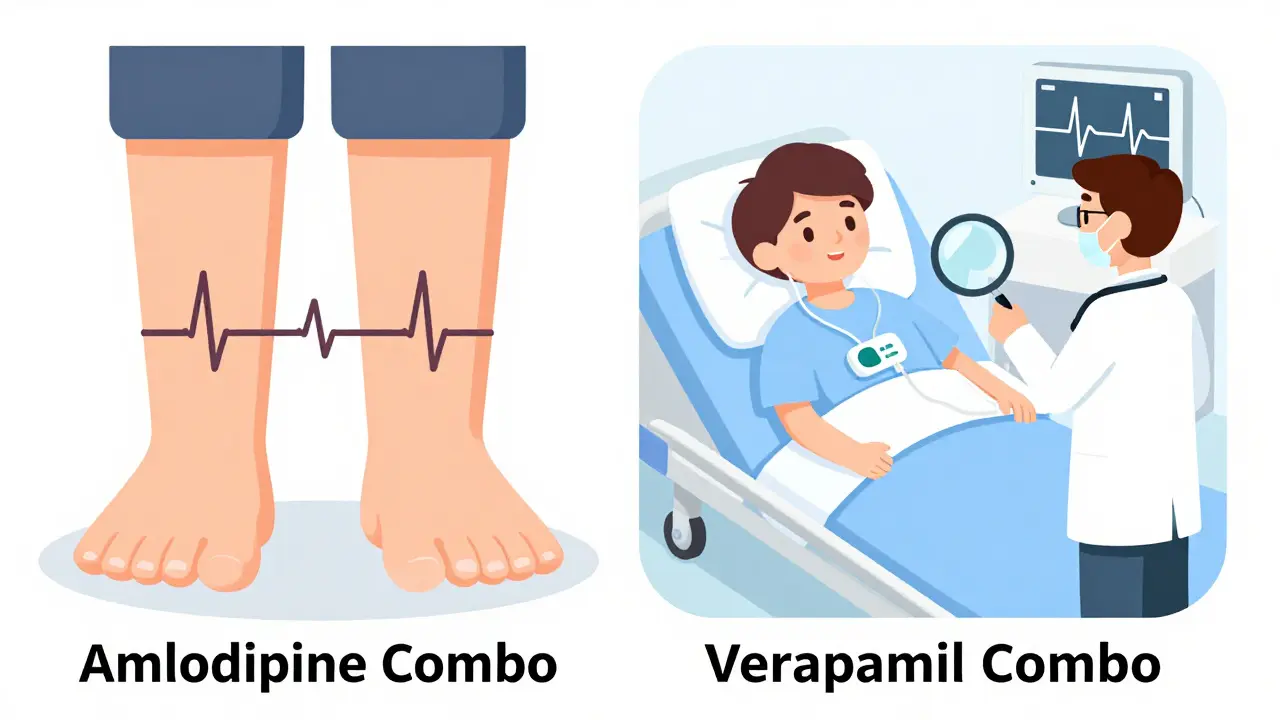

One cardiologist in Boston, after 15 years of prescribing this combo, said only 3% of her patients developed ankle swelling-something easily fixed by lowering the amlodipine dose. That’s a world away from the 18.7% discontinuation rate seen with verapamil combos.

Why does this work? Because their mechanisms don’t overlap. Beta-blockers reduce heart rate and force. Amlodipine reduces pressure by relaxing arteries. No double hit on the heart’s electrical system. No dangerous synergy.

Who Should Never Get This Combo?

Some people should never be put on beta-blockers with non-dihydropyridine CCBs. The guidelines are clear:

- Patients with sinus node dysfunction (a slow or irregular natural pacemaker)

- Those with a PR interval longer than 200 milliseconds on ECG (a sign of delayed electrical signal)

- People with second- or third-degree heart block

- Anyone with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)

- Patients over 75 with unknown heart rhythm history

The European Society of Cardiology explicitly says: avoid verapamil with beta-blockers in these cases. The FDA added a boxed warning in 2021. That’s the strongest warning they give.

And it’s not just about age. A 2022 study found that 15% of patients over 75 had undiagnosed conduction problems. They felt fine. Their ECG looked okay. Then they got verapamil. Within weeks, they were in the ER.

What Doctors Should Do Before Prescribing

If a doctor is considering this combo, they shouldn’t just write a prescription. They need to:

- Check an ECG-look at the PR interval and heart rhythm

- Do an echocardiogram-measure the ejection fraction

- Review all other medications-many drugs interact with these

- Start low and go slow-especially in older adults

- Monitor heart rate and blood pressure weekly for the first month

The European Society of Cardiology even has an online calculator that predicts bradycardia risk with 89% accuracy. It asks for age, kidney function, current heart rate, and which drugs are being used. It’s not fancy-but it saves lives.

The Real-World Picture: What Clinicians Are Saying

On the American College of Cardiology’s forum, doctors are blunt:

- “I avoid verapamil with beta-blockers like the plague.” - Dr. Sarah Chen, Massachusetts General Hospital

- “I’ve seen three patients in five years go into complete heart block. All on verapamil + metoprolol.” - Anonymous cardiologist, Reddit

- “If it’s not amlodipine, I don’t combine it with a beta-blocker.” - Dr. James Lin, Chicago

A 2022 survey of 1,247 clinicians showed 78% preferred beta-blockers with dihydropyridine CCBs. Only 12% would even consider verapamil in a patient, and most of those were in rare cases like severe angina with no other options.

And the complaints? Peripheral edema (swelling in the legs) from amlodipine is common-but manageable. Bradycardia from verapamil combos? Not manageable. It’s an emergency.

Why This Combo Still Has a Place

Despite the risks, this combo isn’t going away. It works. For patients with both high blood pressure and angina, especially those who can’t take nitrates or ACE inhibitors, beta-blocker + amlodipine is often the best choice. It reduces chest pain, lowers pressure, and protects the heart without over-sedating it.

And in places like China, where this combo is used more often, outcomes are better than in the U.S. Why? Because Chinese guidelines are more open to it-when used correctly. The key is patient selection. Not every patient. Not every drug. Just the right ones.

What’s Changing in 2026

The European Society of Hypertension is rolling out a new risk tool in late 2025 to help doctors decide who can safely use this combo. Early results show it can cut adverse events by over 40%.

Meanwhile, prescriptions for beta-blocker + dihydropyridine CCBs are growing. GlobalData predicts a 5.7% annual rise through 2028. Verapamil combos? They’re declining. Hospitals like Kaiser Permanente cut their adverse events by 44% after banning verapamil + beta-blockers unless under strict supervision.

The message is clear: if you need this combo, use amlodipine. Avoid verapamil. Check the ECG. Know the patient’s history. Monitor closely. Don’t assume it’s safe just because it’s prescribed.

Can beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers be taken together safely?

Yes-but only under strict conditions. Combining a beta-blocker with a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker like amlodipine is generally safe and effective for many patients with hypertension and angina. However, combining a beta-blocker with a non-dihydropyridine CCB like verapamil or diltiazem carries a high risk of dangerous heart rhythm problems, including bradycardia and heart block. This combination should be avoided unless absolutely necessary and only after thorough testing.

What’s the difference between amlodipine and verapamil when combined with beta-blockers?

Amlodipine is a dihydropyridine CCB that mainly relaxes blood vessels with little effect on heart rhythm. When paired with a beta-blocker, it lowers blood pressure safely and often improves outcomes. Verapamil is a non-dihydropyridine CCB that slows the heart’s electrical signals and reduces pumping strength. Combined with a beta-blocker, it can dangerously slow the heart rate or cause heart block. The risks with verapamil are so high that most experts avoid this combo entirely.

Who should not take beta-blockers with calcium channel blockers?

Patients with sinus node dysfunction, a PR interval longer than 200 milliseconds, second- or third-degree heart block, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, or those over 75 with unknown heart rhythm issues should not receive this combination-especially if verapamil or diltiazem is involved. These patients are at high risk of life-threatening bradycardia or complete heart block. Guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and the FDA explicitly warn against it.

What tests should be done before starting this combination?

Before starting a beta-blocker with a calcium channel blocker, doctors should perform an electrocardiogram (ECG) to check the PR interval and heart rhythm, and an echocardiogram to measure left ventricular ejection fraction. Baseline heart rate and blood pressure should also be recorded. For patients over 65 or with kidney disease, additional monitoring is recommended. Weekly checks for the first month are standard practice.

Is this combination more common in certain countries?

Yes. In China, beta-blocker + CCB combinations are used in 22% of dual therapy cases, largely because guidelines are more permissive and amlodipine is widely available. In the U.S., the rate is only 12%, and most doctors avoid verapamil combos entirely. The difference comes down to clinical culture, guideline interpretation, and access to monitoring tools. In Australia, where guidelines follow Europe closely, the preference is strongly for amlodipine-based combinations.

What are the long-term risks of using this combo?

Long-term use of beta-blockers with verapamil or diltiazem increases the risk of heart failure hospitalization by nearly threefold compared to amlodipine combos. It also raises the chance of needing a pacemaker due to slow heart rhythms. Even if patients feel fine at first, the cumulative effect on heart function can be silent but damaging. Amlodipine-based combos, however, show no increased long-term risk and may even reduce heart failure progression in high-risk patients.

Comments(13)