Side Effect Type Checker

How the Tool Works

This tool helps determine whether a medication side effect is most likely:

Type A (Dose-Related) or Type B (Non-Dose-Related)

Based on your answers to the questions below, we'll provide a likely classification with explanations from pharmacology principles.

Side Effect Information

When you take a pill, you expect it to help - not hurt. But sometimes, medications cause side effects. Some are predictable. Others come out of nowhere. The difference between them isn’t just academic - it can mean the difference between adjusting your dose and needing an emergency room visit.

What Are Dose-Related Side Effects?

Dose-related side effects, also called Type A reactions, happen because the drug is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do - just too much. They’re predictable, common, and tied directly to how much of the drug is in your system.

Think of insulin. If you take too much, your blood sugar drops too low. That’s not a mistake in the drug - it’s an extension of its action. Same with blood pressure pills: if your systolic pressure falls below 90 mmHg after a dose, that’s a classic dose-related reaction. Or warfarin: if your INR climbs above 4.0, you’re at serious risk of bleeding.

These reactions follow the law of mass action - more drug, more effect. They’re the reason doctors start with low doses and go slow. Drugs like lithium, digoxin, and phenytoin have narrow therapeutic indices, meaning the gap between a helpful dose and a toxic one is tiny. Digoxin’s safe range? 0.5 to 0.9 ng/mL. Above 2.0? Toxic. Lithium? Safe at 0.6-1.0 mmol/L. Over 1.2? Dangerous.

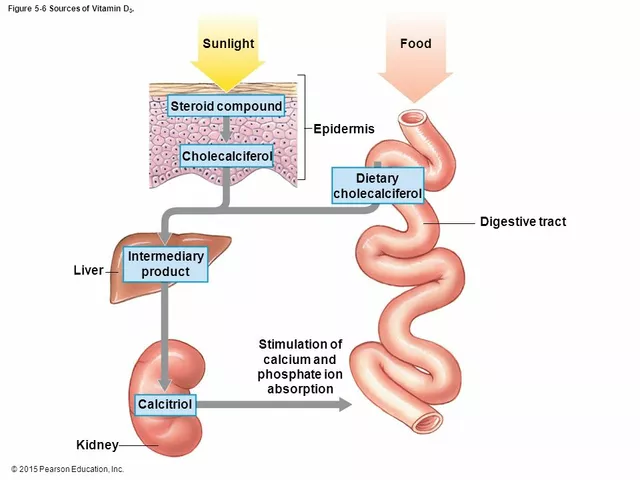

Why do these happen? Often, it’s because of other factors. Kidneys slowing down with age? That means drugs like metformin or enoxaparin build up. A new antibiotic like clarithromycin blocking the enzyme that breaks down your statin? That can spike statin levels by 5 to 10 times. Elderly patients clear diazepam 30-40% slower. All of these turn a normal dose into a dangerous one.

These reactions make up 70-80% of all adverse drug reactions. They’re responsible for 67% of emergency visits in adults over 65. And while they rarely kill - under 1% mortality - they’re the reason most hospitalizations from medications happen.

What Are Non-Dose-Related Side Effects?

Non-dose-related side effects, or Type B reactions, are the opposite. They’re unpredictable, rare, and don’t follow the rules of pharmacology. You could take 10 mg or 100 mg - if your body reacts, it reacts. No warning. No dose threshold that works for everyone.

These are usually immune-driven. Anaphylaxis to penicillin. Stevens-Johnson syndrome from lamotrigine. Drug-induced liver injury from amoxicillin-clavulanate. These aren’t about how much you took. They’re about who you are.

One patient takes one 500mg dose of amoxicillin and breaks out in a full-body rash. Another takes 10 times that dose with no issue. Why? Genetics. Immune history. Random chance. The reaction doesn’t scale with dose. It’s all-or-nothing.

And here’s the scary part: Type B reactions can happen on the first dose - even if you’ve never had the drug before. That’s because you might have been sensitized earlier, maybe by a different drug, or even an infection that tricked your immune system into reacting to the medicine later.

They’re rare - only 15-20% of all adverse reactions - but they cause 70-80% of serious ADR-related hospitalizations and nearly all drug withdrawals from the market. Their mortality rate? 5-10%. That’s why a single case of Stevens-Johnson syndrome can shut down a drug’s entire use.

Why Do Some Reactions Seem Non-Dose-Related When They’re Not?

It’s a common misunderstanding. Just because a reaction doesn’t seem to get worse with higher doses doesn’t mean there’s no dose involved. The real explanation? Three things:

- Hypersusceptibility: Some people hit their maximum reaction at 1 mg. For them, 5 mg isn’t worse - it’s the same. The curve is flat after the first tiny dose.

- Wide individual differences: One person’s toxic dose is another’s placebo. Genetic variations in liver enzymes or immune receptors make this chaos.

- Measurement errors: We often don’t know the real dose someone took. Did they skip a dose? Take an extra one? Use a different brand? We assume the label dose, but reality is messier.

Dr. Jeffrey Aronson, a leading pharmacologist, puts it simply: “Type B reactions aren’t truly dose-independent. They’re dose-unrelated - because the threshold varies so wildly between people that we can’t predict it.”

How Doctors Tell Them Apart - And What They Do

Knowing the difference changes everything.

For Type A reactions, the fix is simple: lower the dose. Or stop the interacting drug. Or monitor levels. Doctors use therapeutic drug monitoring for drugs like vancomycin (target trough 10-20 mg/L), digoxin (0.5-0.9 ng/mL), and phenytoin (10-20 mcg/mL). For kidney patients, they cut enoxaparin doses by half. For liver disease, they slash dronedarone by 75%.

For Type B reactions? There’s no dose tweak that helps. The only safe move is to stop the drug - forever. And avoid anything similar. If you had anaphylaxis to penicillin, you won’t get amoxicillin either. If you got Stevens-Johnson from carbamazepine, you’re at risk with other aromatic anticonvulsants.

That’s why genetic testing matters. Before giving abacavir (an HIV drug), doctors test for HLA-B*57:01. If you have it, your risk of a life-threatening reaction jumps from less than 1% to over 50%. Testing costs $150-300 - but it prevents hospitalizations that cost $50,000+. The FDA now requires this test for 28 drugs. In Asia, testing for HLA-B*15:02 before carbamazepine cuts SJS risk by 97%.

Even penicillin allergies can be tested. Skin testing has a 50-70% positive predictive value. If it’s negative, a graded challenge - slowly giving small doses under supervision - works 80-90% of the time.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Older adults. People with kidney or liver disease. Those on five or more medications. And people with certain genes.

Type A reactions hit older patients hardest. Their bodies don’t clear drugs well. Their organs are slower. Their diets change. Their prescriptions pile up. That’s why anticoagulants, insulin, and oral hypoglycemics cause most emergency visits in seniors.

Type B reactions? They’re more random - but genetics play a huge role. HLA-B*57:01 carriers. CYP2C9 variants that make warfarin too potent. TPMT mutations that turn azathioprine into a poison. These aren’t lifestyle issues. They’re coded in your DNA.

And here’s the kicker: 68% of clinicians correctly identify Type A reactions as dose-dependent. But only 43% know Type B reactions can still have hidden dose thresholds. That gap in knowledge leads to mistakes - like restarting a drug after a Type B reaction because “it was just a high dose.”

The Future: Personalized Dosing and AI

Pharmacogenomics is changing everything. The global market for genetic testing related to drugs is expected to hit $17.9 billion by 2030. The FDA now lists pharmacogenomic info on 311 drug labels. And programs like CPIC give doctors clear rules: “If you have this gene, start with 50% less warfarin.”

Machine learning is helping too. AI models analyzing electronic health records can predict Type A reactions with 82% accuracy. For Type B? Only 63%. Why? Because Type A follows rules. Type B is still mostly mystery.

But the direction is clear: we’re moving toward personalized dosing. Not just “take one pill a day.” But “take this dose based on your age, weight, kidney function, liver enzymes, and genetic profile.” The FDA’s 2024 draft guidance on individualized dosing software signals that this isn’t science fiction - it’s coming.

What You Should Know

If you’ve had a side effect from a medication, ask: Was it dose-related? Or did it happen out of nowhere?

If you got dizzy after a blood pressure pill - that’s likely Type A. Talk to your doctor about lowering the dose. If you broke out in a rash after one tablet of a new antibiotic - that’s Type B. Don’t take it again. Ever. And tell every doctor you see.

Keep a list of all your meds and any side effects you’ve had. Bring it to every appointment. If you’re over 65 or on multiple drugs, ask about drug interactions. If you’re of Asian descent and prescribed carbamazepine, ask about HLA testing. If you’re on warfarin, ask about genetic testing for CYP2C9 and VKORC1.

Side effects aren’t just bad luck. They’re signals. And understanding whether they’re tied to dose - or to your body - is the first step to staying safe.

Are all side effects dose-related?

No. About 70-80% of side effects are dose-related (Type A), meaning they happen because the drug’s effect is too strong. The other 15-20% are non-dose-related (Type B), like allergic reactions or rare genetic responses - they can happen at any dose, even the smallest one.

Can you prevent dose-related side effects?

Yes. Doctors can prevent them by starting with low doses, checking kidney and liver function, avoiding drug interactions, and using therapeutic drug monitoring for medications like digoxin, lithium, or vancomycin. Regular blood tests and clear communication about symptoms help catch problems early.

Why are non-dose-related side effects more dangerous?

Because they’re unpredictable and often severe. They’re not caused by too much drug - they’re caused by your body’s unique reaction to it. That means you can’t avoid them by lowering the dose. Once they happen, you must stop the drug permanently. They’re responsible for most drug withdrawals and black box warnings.

Is genetic testing worth it for avoiding side effects?

For certain drugs, yes. Testing for HLA-B*57:01 before taking abacavir cuts the risk of a life-threatening reaction from 5-8% to under 0.1%. Testing for HLA-B*15:02 before carbamazepine prevents 97% of Stevens-Johnson cases in Asian populations. The test costs $150-300 - far less than an emergency hospital stay.

Can a Type B reaction happen on the first dose?

Yes. Even if you’ve never taken the drug before, your immune system might have been sensitized earlier - by a similar drug, an infection, or even environmental exposure. That’s why some people have anaphylaxis on their very first dose of penicillin. It’s not about the dose - it’s about your body’s prior exposure.

What should I do if I have a side effect?

Don’t ignore it. Note the timing, dose, and symptoms. Call your doctor. If it’s sudden - like swelling, trouble breathing, or a severe rash - go to the ER. Afterward, ask whether it was likely Type A or Type B. Add it to your medication list. And never take the drug again unless your doctor says it’s safe with testing.

Comments(12)