When a life-saving drug suddenly disappears from the shelf, it’s not just an inconvenience-it’s a crisis. In 2022, the U.S. faced 287 medication shortages, affecting nearly one in five essential hospital medications. These aren’t rare glitches. They’re systemic failures that hit hardest in emergency rooms, cancer clinics, and rural hospitals where options are already limited. If you’re a clinician, pharmacist, or even a patient managing chronic conditions, you’ve likely felt the ripple effect: delayed treatments, last-minute substitutions, increased errors, and longer waits. The question isn’t whether a shortage will happen-it’s when, and how prepared are you?

What’s Really Causing These Shortages?

Most people assume drug shortages happen because of high demand or pandemics. But the real root causes are quieter-and more preventable. According to FDA data, 46% of all shortages in 2022 stemmed from manufacturing quality issues. Think contaminated batches, failed inspections, or outdated equipment in facilities that haven’t been upgraded in decades. These aren’t random accidents. They’re often the result of underinvestment in production infrastructure. The problem is worst with generic sterile injectables-drugs like morphine, saline, antibiotics, and chemotherapy agents. These are the backbone of hospital care, but they’re also low-margin products. Manufacturers have little financial incentive to maintain multiple production lines or invest in quality controls when the market rewards the cheapest bid. Just three companies control 75% of the U.S. supply for these critical drugs. One facility shuts down for a quality issue, and the entire country feels it. Add to that the global dependency on foreign suppliers. 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used in U.S. medications come from overseas, mostly China and India. A single factory delay abroad can trigger a cascade of shortages months later. And unlike other industries, there’s no national stockpile to buffer the blow. The Strategic National Stockpile exists for bioterrorism or disasters, not everyday drug gaps.Who Gets Hurt the Most?

Shortages don’t affect everyone equally. Rural hospitals, safety-net clinics, and facilities serving Medicaid or uninsured patients bear the heaviest burden. According to the American College of Physicians, 78% of these facilities have had to cancel or delay procedures because of unavailable drugs. A cancer patient waiting for doxorubicin. A diabetic needing insulin. A child requiring epinephrine during anaphylaxis. These aren’t hypotheticals-they’re daily realities. Nurses report patient wait times increasing by 22 minutes on average for critical medications during shortages. Pharmacists work 12.7 extra hours per week just managing the fallout. And when substitutes are used-like switching from morphine to hydromorphone-medication errors spike by up to 15%. These aren’t just statistics. They’re human consequences. Physicians are forced to make impossible choices: delay surgery, use a less effective drug, or risk a dangerous alternative. In a 2023 AMA survey, 43% of practices said shortages directly altered patient treatment plans. For some, that meant choosing between two life-saving drugs because only one was available.How Hospitals Are Trying to Cope (And Where They’re Failing)

Many hospitals have formed shortage response teams, but too often, they’re reactive, not proactive. The MPRDHRS Demonstration Project found that 87% of pharmacy directors only learn about a shortage when the shipment doesn’t arrive. By then, it’s too late to plan. Effective management requires a structured approach:- A dedicated shortage committee that meets weekly and activates within 4 hours of a shortage alert

- A real-time shortage log tracking: time of discovery, alternatives evaluated, clinical impact, communication timeline, and error rates

- Buffer stock of 14-30 days for critical drugs-though most safety-net hospitals can only afford 8-12 days

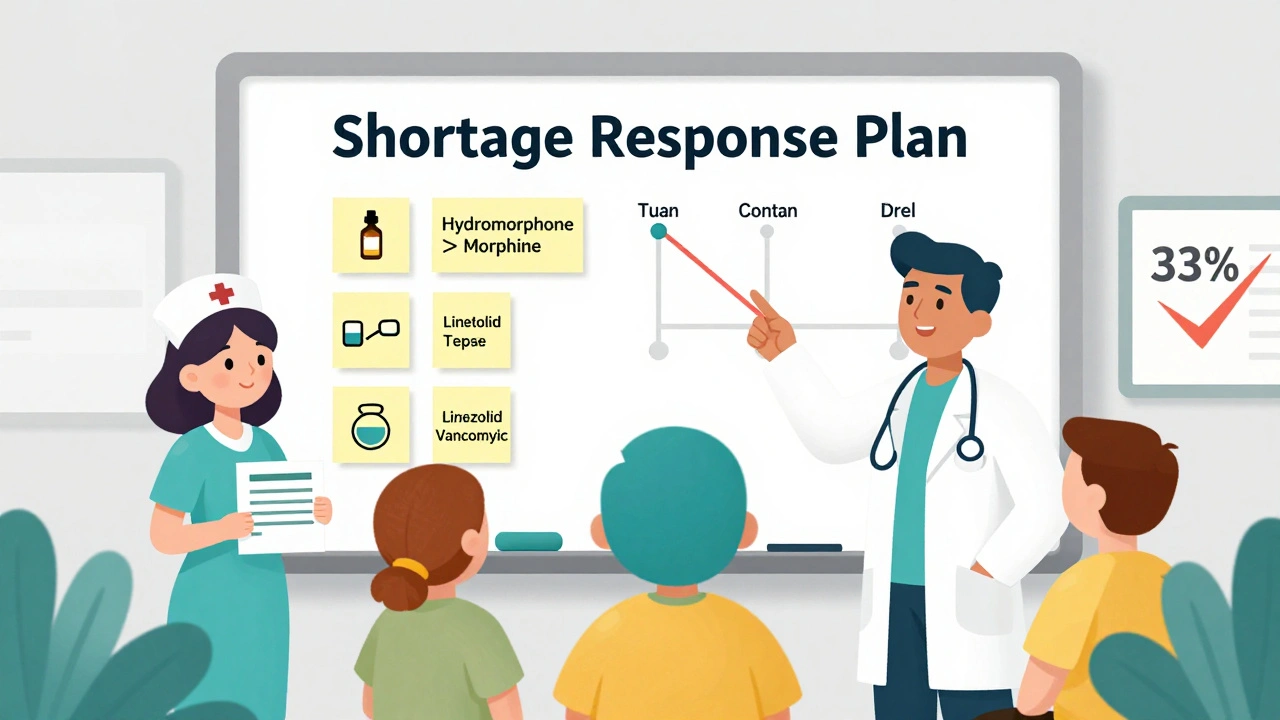

- Staff training through quarterly simulation drills, which have been shown to reduce errors by 33% during actual shortages

What Can You Do Right Now?

You don’t need to wait for federal policy to change to protect your patients. Here’s what works today:- Monitor the FDA Drug Shortage Database daily. It’s updated in real time and lists active shortages, expected resolution dates, and manufacturer contacts. Bookmark it. Set up alerts.

- Build a list of approved alternatives for your top 10 most critical drugs. Include dosing conversions, compatibility notes, and contraindications. Update it every quarter.

- Partner with regional pharmacy networks. Many hospitals in the same area share inventory during shortages. Formalize that relationship now, before a crisis hits.

- Train your team on substitution protocols. Don’t rely on one pharmacist’s memory. Create quick-reference cards for common swaps-like using norepinephrine instead of dopamine in shock, or switching from vancomycin to linezolid for MRSA.

- Document every substitution and outcome. If you give a patient an alternative drug, record why, what was given, and how they responded. This data helps your hospital advocate for better supply chain policies later.

Why the System Isn’t Fixing Itself

The U.S. relies on voluntary reporting by manufacturers under Section 506C of the FD&C Act. But compliance? Only 65%. That means nearly a third of shortages are announced late-or not at all. Meanwhile, countries like France and Canada have mandatory reporting systems that cut shortage duration by 37%. The economic structure is broken. Medicaid and 340B programs pay fixed, low prices for generics. Manufacturers can’t raise prices to cover quality upgrades because those programs won’t reimburse more. So they cut corners-and shortages follow. Experts like Dr. Scott Gottlieb and the Brookings Institution argue that Medicare Part B reimbursement should reward reliability, not just lowest cost. Imagine if a hospital got paid more for using a drug from a manufacturer with a proven track record of consistent supply. That would change behavior overnight.

What’s Changing? And What’s Next?

There are signs of progress. In 2022, HHS created the Supply Chain Resilience and Shortage Coordinator role to centralize response efforts. The FDA’s draft guidance on Risk Management Plans for manufacturers is expected to be finalized in mid-2024. If enforced, it could require companies to map their supply chains, identify single points of failure, and have backup plans ready. Some manufacturers are experimenting with advanced production technologies-like modular, flexible manufacturing lines that can switch between drugs in hours instead of weeks. If adopted widely, this could reduce shortages by 40%. But long-term, without policy changes, the trend is clear: the Congressional Budget Office predicts shortages will grow by 8-12% annually through 2030, especially for oncology, anesthesia, and critical care drugs.Final Thought: Preparedness Is the Only Reliable Drug

You can’t control whether a drug will be available. But you can control how you respond. The hospitals that survive shortages aren’t the ones with the biggest budgets. They’re the ones with the clearest plans, the most trained staff, and the most honest conversations with their teams. Start small. Pick one critical drug your facility uses. Find its alternatives. Train two people on how to switch safely. Document it. Share it. Repeat. Because when the next shortage hits-and it will-you won’t have time to read a policy paper. You’ll need to act. And the difference between chaos and calm will be what you did yesterday.How often do medication shortages happen in the U.S.?

In 2022, the FDA recorded 287 active drug shortages, affecting nearly 19% of essential hospital medications. While numbers dipped slightly in 2016 due to regulatory efforts, they’ve been rising again since 2020. The trend shows no sign of slowing, with projections indicating an 8-12% annual increase through 2030, especially for cancer, anesthesia, and critical care drugs.

What are the most commonly affected drugs?

Generic sterile injectables make up 63% of all shortages. These include morphine, saline, antibiotics like vancomycin and cefazolin, chemotherapy agents like doxorubicin and cisplatin, IV nutrition, and crash cart drugs like epinephrine and atropine. These are used daily in emergency rooms, ICUs, and operating rooms-making their unavailability especially dangerous.

Can I legally substitute one drug for another during a shortage?

Yes, but only if the alternative is approved by your institution’s pharmacy and therapeutics committee and is clinically appropriate. Substitutions must be documented, and dosing conversions must be accurate. For example, hydromorphone can replace morphine, but the dose must be adjusted (typically 1:5 ratio). Never substitute without checking compatibility, contraindications, and institutional policy.

How can I find out if a drug is in shortage?

Check the FDA’s Drug Shortage Database, updated daily. It lists active shortages, expected resolution dates, manufacturer contacts, and alternative options. Many hospitals also subscribe to ASHP’s Drug Shortage Resource Center or use pharmacy management software with built-in shortage alerts. Don’t wait for a delivery to fail-monitor proactively.

Why don’t hospitals just stockpile more drugs?

Cost and storage are major barriers. Many critical drugs have short shelf lives, require special storage (like refrigeration or sterile conditions), and are expensive to buy in bulk. Safety-net hospitals, in particular, often can’t afford to hold more than 8-12 days of inventory, even though experts recommend 14-30 days. Without reimbursement changes that reward preparedness, stockpiling remains financially unsustainable for most facilities.

Are there any global solutions that work better than the U.S. system?

Yes. Countries like France and Canada require mandatory reporting of potential shortages, which reduces average duration by 37%. Germany maintains national strategic stockpiles for critical medications, cutting impact by 52% during recent crises. These systems prioritize continuity of care over lowest-cost procurement-something the U.S. still struggles to adopt.

Comments(11)